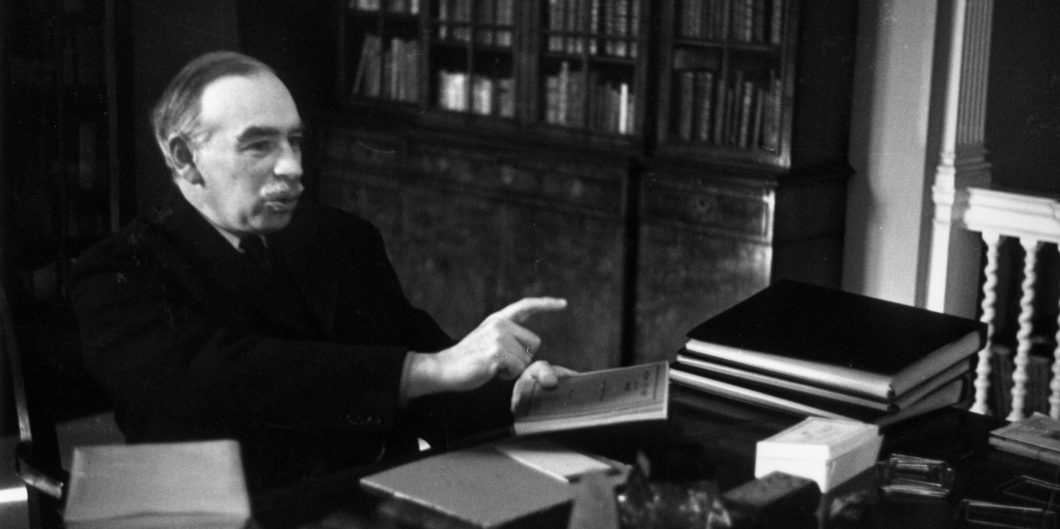

On November 6, 1924, a tall Cambridge economist stood up and delivered the fourth annual Sidney Ball Memorial Lecture at Oxford University. Then, as now, public lectures allowed distinguished scholars to weigh in on sundry issues outside strictly academic settings. But John Maynard Keynes’s now 100-year-old address, “The End of Laissez-Faire,” was no ordinary set of remarks. It foreshadowed a revolution in economic thought that eventually transformed the world’s economic landscape.

Even in its revised and published form, Keynes’s lecture is not especially systematic. Several of its key points remained severely underdeveloped. Yet, despite these limitations, “The End of Laissez-Faire” was a decisive step in Keynes’s decades-long effort to expand the state’s role in the economy. Success in realizing this objective was preconditioned upon Keynes persuading his listeners that laissez-faire economics had had its day.

By “laissez-faire,” Keynes meant the economic vision grounded upon free markets, limited government, and the pursuit of individual self-interest first systematically outlined by Adam Smith. Throughout the nineteenth century, Keynes argued, this conception of economics had attained a hegemony among most economists. Keynes was, however, convinced that market liberalism could not comprehend or cope with the post-1918 world’s economic problems. In his view, this necessitated a thorough rethinking of both economics and economic policy. The results of Keynes’s subsequent endeavors surround us today in the form of economically activist governments that crowd out freedom to an extent not even Keynes himself may have anticipated.

Going to the Roots

In the months preceding his Sidney Ball lecture, Keynes had signaled his growing doubts about market liberalism. In two articles published in The Nation in May 1924, Keynes argued that it could no longer be assumed that market forces would eventually restore full employment. Getting the British economy out of its protracted slump required, Keynes stated for the first time, “an impulse, a jolt, an acceleration” through means like public works or forcing a shift in British savings away from foreign markets towards domestic investment.

In the “End of Laissez-Faire,” Keynes takes a different tack. Rather than discussing policy, he goes straight to market liberalism’s philosophical roots. Keynes traces these to Enlightenment sources like John Locke’s conception of natural liberty and David Hume’s stress on utility. The power of these ideas of “conservative individualism,” as well as the influence of such unlikely nineteenth-century bedfellows like Charles Darwin and Archbishop Richard Whately, Keynes maintains, created conditions whereby citizens and governments alike came to believe that individuals’ pursuit of self-interest, combined with an absence of government intervention, had produced unprecedented economic, social, and political flourishing.

According to Keynes, the contribution of economists to this widespread confidence in markets was to associate laissez-faire thought with “scientific proof that [government economic] interference is inexpedient.” Further reinforcement of laissez-faire’s dominance, Keynes states, proceeded from the fact that “material progress between 1750 and 1850 came from individual initiative, and owed almost nothing to the directive influence of organized society as a whole.” Thus, he concludes, “practical experience reinforced a priori reasoning.”

Repudiating a whole set of a priori positions was central to Keynes’s attempt to prove market liberalism’s redundancy by discrediting its underlying intellectual apparatus. He declares, for instance, “It is not true that individuals possess a prescriptive ‘natural liberty’ in their economic activities.” Precisely why this claim (labeled “metaphysical” by Keynes) is false goes unexplained. Similarly, Keynes insists that “more often individuals acting separately to promote their own ends are too ignorant or too weak to attain even these.” Again, Keynes offers no evidence to support this assertion, even by way of footnotes.

Goodbye to Theory

Driving Keynes’s determination to smash holes in market liberalism’s intellectual underpinnings was his desire to clear the way for extensive government economic interventions. Keynes was well aware that the wisdom of such interventions would be disputed on grounds of economic theory. His response was to marginalize the saliency of economic theory itself.

One consistency pervading Keynes’s thought from the 1920s onwards is his conviction that the facts and problems confronting us must drive action, with theory being subordinated to the demands of praxis. Keynes’s lecture does not hide his impatience with market-liberal economists and their perpetual concern for sound theory.

Laissez-faire, from Keynes’s standpoint, had gradually come to function as a kind of ideology, and its theoretical underpinnings tended to collapse into dogma. In his view, this was exemplified by the writings of the nineteenth-century French economist Frédéric Bastiat. Here, Keynes said, “We reach the most extravagant and rhapsodical expression of the political economist’s religion.” For too many economists, Keynes stipulated, “The beauty and the simplicity of such a theory are so great that it is easy to forget that it follows not from the actual facts, but from an incomplete hypothesis introduced for the sake of simplicity.”

Economic theories are indeed abstract and often posed as hypotheticals. They are also subject to constant reverification. Keynes, however, downplays their indispensable role in comprehending and responding to economic reality. Facts after all do not explain themselves. Absent a coherent theoretical framework, it is impossible for economists to understand the significance of millions of pieces of data, or grasp how ever-growing and changing sets of facts relate to each other.

Indeed, without solid theory, we find ourselves reverting to experience, intuition, or varying combinations of such things to explain reality. While they have their uses, peoples’ experiences and intuitions often radically differ, frequently contradict each other, and themselves require explanation. Their reliability as a way of organizing our thoughts, understanding the world, or guiding economic policy is thus constrained.

In the long-term, Keynes’s proposals for addressing the high unemployment of the 1930s would contribute substantially to the high unemployment and runaway inflation of the 1970s.

Keynes, however, skips over such objections. “We cannot,” he contends, “settle on abstract grounds” the parameters of what the state can and cannot do in the economy. Rather, we “must handle on its merits in detail what Burke termed ‘one of the finest problems in legislation, namely, to determine what the State ought to take upon itself to direct by the public wisdom, and what it ought to leave, with as little interference as possible, to individual exertion.’”

Recruiting Edmund Burke as an ally is a questionable move, given the way that writings like his “Thoughts and Details on Scarcity” accorded a significant role to economic theory in determining the limits of state intervention. In any event, Keynes’s words suggest a case-by-case approach to intervention. As if, however, he recognizes the inescapability of some type of intellectual framework to order our decision-making about what governments should and should not do, Keynes distinguishes between “those services which are technically social from those which are technically individual.”

The “technically social,” Keynes says, are those “decisions which are made by no one if the State does not make them.” While that sounds like a public goods argument, Keynes’s “technically social” turns out to involve not only an incipit embrace of state macro-management of the economy but also full-blown corporatism.

Keynes the Corporatist

One of market liberalism’s failures, Keynes claimed in his lecture, was its inability to address problems generated by the prevalence of “risk, uncertainty, and ignorance” in the economy. These, he stated, produced “great inequalities of wealth” and “are also the cause of the unemployment of labour, or the disappointment of reasonable business expectations, and of the impairment of efficiency and production.”

Keynes deemed it possible to minimize these difficulties through “deliberate control of the currency and of credit by a central institution.” Another of Keynes’s “technically social” policies involved state agencies collecting and disseminating “on a great scale” all “data relating to the business situation, including the full publicity, by law if necessary, of all business facts which it is useful to know.”

How we distinguish useful from non-useful facts is not specified. But such information, Keynes insists, must be collated so that “society” can exercise “directive intelligence through some appropriate organ of action over many of the inner intricacies of private business.”

This, Keynes hastens to add, “would leave private initiative and enterprise unhindered.” Keynes, however, does not elucidate why this is the case—perhaps because he cannot. Indeed, one reason why Keynes underscores the need for a government agency to assemble business facts is his belief that:

some coordinated act of intelligent judgement is required as to the scale on which it is desirable that the community as a whole should save, the scale on which these savings should go abroad in the form of foreign investments, and whether the present organization of the investment market distributes savings along the most nationally productive channels. I do not think that these matters should be left entirely to the chances of private judgement and private profits, as they are at present.

In other words, Keynes does want to hinder the workings of private initiative and enterprise by means of “the community as a whole” making decisions about the aggregate distribution of savings between domestic and foreign investments.

Things get even more complicated once we discern what Keynes means by “society” and “the community.” In some cases, this functions as Keynesian shorthand for direct state intervention. In other instances, Keynes holds that “many big undertakings, particularly public utility enterprises and other business requiring a large fixed capital … need to be semi-socialized.”

By “semi-socialism,” Keynes has in mind something akin to “medieval conceptions of separate autonomies.” In general, he comments, we should “prefer semi-autonomous corporations to organs of the central government for which ministers of State are directly responsible.” As examples, Keynes suggests institutions like universities, the Bank of England, and railway companies, all of which operated at one or more removes from the state but whose legal status was not that of a strictly private association. “In Germany,” Keynes observes in a casual aside, “there are doubtless analogous instances.”

That reference indicates Keynes’s awareness of corporatism’s influence throughout the early-twentieth-century German-speaking world. Nor should we forget that corporatism had become official government policy in Italy following Mussolini’s seizure of power just two years before Keynes’s laissez-faire lecture. In short, corporatist ideas that posited the corralling of individuals into state-supervised groups and promoted the public-private amalgams envisaged by Keynes were “in the air”—and the Cambridge don had breathed deeply.

A Heavy Legacy

In this and other ways, Keynes’s “End of Laissez-Faire” amounted to more than an effort to kill off market liberalism. It prefigured Keynes’s ambition to design economic policies which were simultaneously shaped by, and sought to influence, contemporary conditions. Ultimately, these would come to fruition in his General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936). But as F. A. Hayek pointed out in his 1972 monograph A Tiger by the Tail, while Keynes had called his book “a ‘general theory,’” it was no such thing. In Hayek’s words, it was “too obviously a tract for the times, conditioned by what he thought to be the momentary needs of policy.”

In the long-term, Keynes’s proposals for addressing the high unemployment of the 1930s would contribute substantially to the high unemployment and runaway inflation of the 1970s. Nonetheless, those same ideas’ popularity cemented in many people’s minds the illusion that governments can somehow “manage” trillion-dollar economies consisting of millions of people from the top down.

A century after Keynes’s “End of Laissez-Faire” lecture, faith in economic interventionism persists across the political spectrum. Immense bureaucracies exist whose entire raison d’être is to enforce core precepts of Keynesian doctrines by pursuing commensurate policies. Keynes may not have succeeded in terminating market liberalism’s influence, but his ideas and their institutional manifestations weigh heavily on us today.